Nigeria turns 60: Can Africa's most populous nation remain united?

Nigeria turns 60: Can Africa's most populous nation remain united?

How to keep a multitude of ethnic groups united and satisfied? This was the greatest hurdle Nigeria faced in the first decade of its independence - and continues to be the case 60 years later.

Heated national conversations usually revolve around which ethnic group gets what, when, and how. Or how fairly a person from one group was treated compared to one from another.

A major policy to promote systemic equality was launched by the Nigerian government almost four decades ago, but it has led to further balkanisation and bitterness.

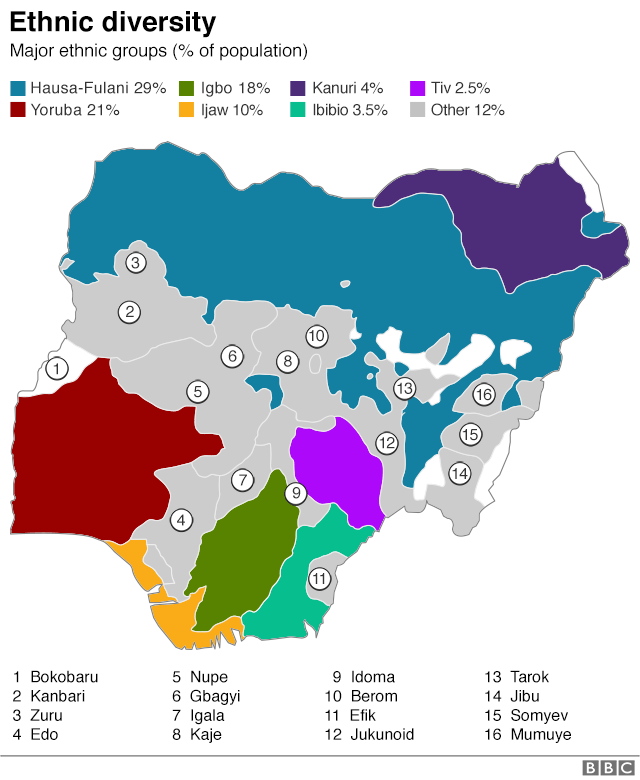

Nigeria is home to more than 300 ethnic groups and three dominant ones: the Igbo in the south-east, the Yoruba in the south-west, and the Hausa in the north.

These groups were separate entities before the British merged them into one country that today operate as a federal system - with power concentrated at the centre and distributed among the 36 states and the capital, Abuja.

Struggles for power at the centre or concerns about unfair treatment have at different times led to pogroms, protests and violent conflict, including the civil war of 1967 to 1970, sparked by an attempt by the Igbo to secede and form a new nation called Biafra.

To foster inclusion, the "federal character principle" was enshrined in Nigeria's 1979 constitution.

It includes a provision for public institutions to reflect the "linguistic, ethnic, religious and geographic diversity of Nigeria".

At first, this seemed to appease all sections of the country.

Educational divide

But, today, it is one of the most contentious government policies, with many Nigerians complaining that it has done more damage to our country than good.

Local newspapers regularly feature headlines such as: "Federal Character a curse to Nigeria" or "Group calls for an end to Federal Character".

For starters, "federal character" was not accompanied by any strategy to end the vast educational inequality that has always existed between Nigeria's majority Muslim north and mainly Christian south.

This disparity is the result of a complex combination of factors, such as religion, culture, past colonial policies and, more recently, the Islamist militant Boko Haram insurgency.

Nigeria has 13 million out-of-school children, the highest in the world, according to Unicef, and more than 69% of them are in the north.

As a result, the region has Nigeria's lowest literacy rates, with some states recording just 8%.

Yet, this same region must still fill its quota in public institutions - quite a massive chunk since it has a population of 90 million out of Nigeria's 200 million, and 19 of 36 states, plus Abuja, totalling 20.

"Regrettably, 'federal character' has become a euphemism for recruiting unqualified people into the public service," said Ike Ekweremadu, a former deputy president of Nigeria's senate.

"These employees decrease productivity, weaken our public service, and ultimately render it inefficient."

These unqualified can easily rise above their more qualified colleagues, as "federal character" is also applied when filling senior positions in public institutions.

In addition, rivalry between ethnic groups often leads people to lift as many of their kinsmen as they can once they find themselves in a position to do so.

Northerners have ruled the country for 38 out of Nigeria's 60 years of independence, mostly via military coups.

I have listened to many Nigerians tell bitter stories of working hard without reward while some colleagues simply lounged their way to promotion because their kinsman was in power.

Thanks to "federal character", ethnic solidarity and striving to be in positions of authority tend to take pre-eminence over self-improvement and excellence.

Reference.

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-54357810

Comments

Post a Comment